Black Lives and The GCC Network

by Ola Jimoh (Initiative Assistant, GCC and HOPE SF) and Monet Boyd (Program Coordinator, GCC)

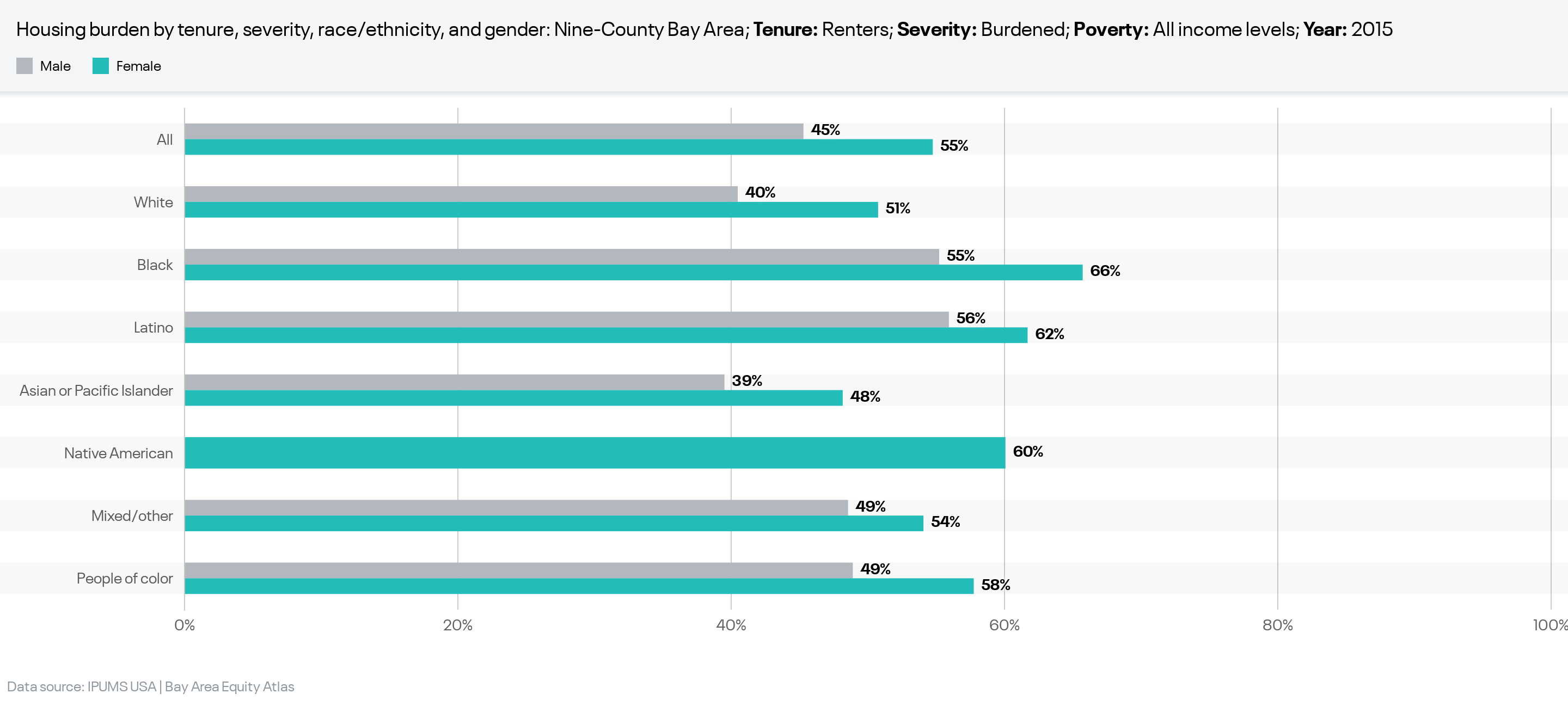

The Great Communities Collaborative (GCC) works within the nine-county Bay Area, which houses a high number of Black residents. Due to systemic racism, Black communities in the Bay Area have faced rent and housing disparities for generations. Black people have dealt with being pushed out of their communities, predatory lending, exclusionary zoning and so much more. According to 2015 data from the Bay Area Equity Atlas, 61% of Black renters were housing burdened, meaning that they spent more than 30% of their income on rent and utilities. Moreover, disaggregating the data by race and gender reveals that Black women were the most housing burdened group; in 2015, 66% of Black female renters across all income levels were housing burdened. In 2019, Black people represented about 5.5% of California’s population; however, of the 150,000 people that experienced homelessness across the state, almost 30% were Black, according to HUD. This data shows that the housing crisis in the Black community is not a new issue, but a pervasive and persistent problem.

The ongoing global pandemic has exacerbated the housing burden for Black people in the Bay Area. For example, according to Bay Area County Public Health Departments, Latinos have disproportionately tested positive for COVID-19 in the Bay Area’s three largest counties (San Francisco, Alameda, and Santa Clara), while Black people have died from the disease at nearly twice the rate of any other race. Black people are also over-represented in low-wage jobs that cannot transition to remote work. These conditions, stay-at-home orders, and other public health measures have disproportionately impacted the Black community. This example illustrates the ways in which Black residents are highly affected by communal conditions that connect to housing, health, economics, and much more. It also highlights the significant need to focus and uplift this community.

By investing more time and resources into the Black community we can better embody racial equity. An example of this work is the HOPE SF Racial Equity and Reparations Guide, developed to acknowledge and address the systemic harm caused by public policy, government agencies, and the marketplace in southeastern San Francisco. HOPE SF is the nation’s first large scale community development and reparations initiative aimed at creating vibrant, inclusive, mixed-income communities without mass displacement of original residents. Its reparations framework places “particular focus on the historical, current, and future path for African Americans because of the legacy of slavery and white supremacy as it targeted African Americans, because African Americans have made up the majority of households in the HOPE SF communities, and because of the pervasive nature of racism experienced by multiple generations of African Americans in San Francisco dating back to World War II.” Moreover, the framework emphasizes the idea that taking a racial equity and reparations approach will benefit us all—not just those who have suffered from harm, but those who have benefitted from harm. These benefits are possible by creating opportunities for economic prosperity, healing, social cohesion, cultural vitality, and transformative justice, which will then uplift morality as well as community voice.

HOPE SF’s reparations framework identifies ways that not only community members, but also housing developers, funders, and local organizations can advance racial equity and reparations by taking an explicit stance for a successful future for the Bay Area. Researchers express that this successful future is dependent on the social and economic inclusion of people of color, on examining and counteracting personal implicit bias, and informing oneself and others of the history and current context of racism and marginalization. Taking these steps elevates and centers the voices of those who are most directly impacted by the legacy of racism. It also promotes the resilience and beauty of these communities in order to systematically change institutions and organizations. HOPE SF was able to implement these ideals by allowing residents to shape decisions, requiring 1-for-1 replacement of public housing without displacement, eviction prevention, and much more. This framework is a model that the GCC network can use to identify areas of strength, as well as gaps in how this shows up in our work and those we serve.

The recent civil unrest within the Black community has brought many pre-existing issues that Black residents face to the forefront. As a collaborative, we have the opportunity to support our partners, address racial disparities and learn from other frameworks to ensure there is a level of intentionality to better serve the Black community. Earlier this summer, GCC’s Initiative Officer and Director, Elizabeth Wampler, mentioned some potential areas of focus we should consider for our conversations. Additionally, we must investigate how our strategies and work are dismantling the impacts of systematic racism to further examine how our network can give more time and effort to the Black community. By considering and using data around Bay Area’s housing burden, gentrification, and COVID-19 disparities as learnings, we can use the power of our network to create greater access to resources and opportunities for Black residents.